“It is curious to see America, the United States, looking on herself, first,

as a sort of natural peacemaker, then as a moral protagonist in this terrible time.

No nation is less fitted for this role. For two or more centuries America has

marched proudly in the van of human hatred…to your tents…

and world war with black and parti-colored mongrel beasts!”

—W.E.B. Du Bois, Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil, 1920

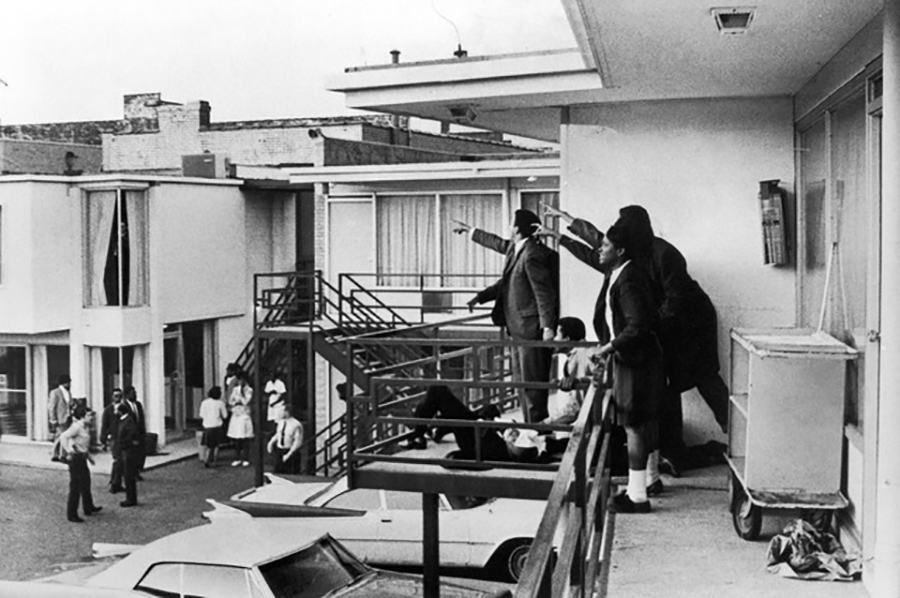

Today, April 4, 2018, is the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., exactly one year after he delivered that remarkable speech Beyond Vietnam – A Time To Break the Silence at Riverside Church in New York City —a brilliant yet controversial speech that connected the Vietnam War to the abysmal living conditions of many black Americans. A speech he knew he had to deliver despite the unanimous verdict of allies and supporters alike, including the “liberal press,” that it would do irreparable harm to the civil right movement.

“…as I have moved to break the betrayal of my own silences…as I have called for radical departures from the destruction of Vietnam…many persons have questioned me about the wisdom of my path…And when I hear them…I am nevertheless greatly saddened…their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.”

The cries of disapproval were swift and biting. On April 7, three days after his speech, the New York Times solidified their reputation as the media’s official “Wrong Way Corrigan” in an editorial entitled “Dr. King’s Error: “the political strategy of uniting the peace movement and the civil rights movement could very well be disastrous for both causes…The Negroes need all the leadership…they can summon…and under these circumstances …Dr. King makes too facile a connection between the speeding of the war in Vietnam and the slowing down of the war against poverty.”

Four days after The Times pooh-poohed the notion of a “slowing down of the war against poverty,” President Johnson signed his last civil rights legislation. The Great Society’s war on poverty had come crashing to a halt as the Vietnam War gobbled up more and more of America’s treasure. Dr. King was right — the needs of the poor and oppressed were the first to get the budget axe.

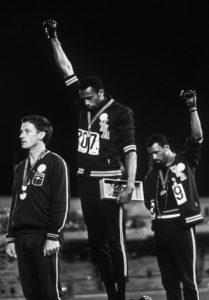

America’s moral compass grew increasingly wobbly during the sixties as controversy over the Vietnam War escalated into debates on civil rights, economic justice, the power of the rich and powerful, gender equality (in 1968, Yale University, 250 years too late, began to admit women to its undergraduate college)  and on the schism between the right of the people to protest and the authoritarian push by a tiny minority of political elites to stifle dissent. In a little know decision, the Warren Court (named for its Chief Justice Earl Warren) famous for declaring segregation illegal [Brown v. Board of Education] and five years later ruling that abortion was a fundamental right under the U.S. Constitution [Roe v. Wade) ruled on May 27, 1968, that draft card burnings were not free speech and thus not protected under the first amendment. In a curious backflip forty-two years later, the Supreme Court to ruled that political spending was a form of protected speech under the First Amendment. [Citizens United v. FEC]

and on the schism between the right of the people to protest and the authoritarian push by a tiny minority of political elites to stifle dissent. In a little know decision, the Warren Court (named for its Chief Justice Earl Warren) famous for declaring segregation illegal [Brown v. Board of Education] and five years later ruling that abortion was a fundamental right under the U.S. Constitution [Roe v. Wade) ruled on May 27, 1968, that draft card burnings were not free speech and thus not protected under the first amendment. In a curious backflip forty-two years later, the Supreme Court to ruled that political spending was a form of protected speech under the First Amendment. [Citizens United v. FEC]

The chicken may have come home to roost in 1968, but President Truman opened the Pandora’s box that became the conundrum of Vietnam with his support of the French drive to re-colonize Vietnam after World War II. That fateful decision came to define the administrations of four succeeding Presidents, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon. In 1968, President Johnson pulled out all the stops in an effort to win the Vietnam War— incessant bombings, a steady buildup of U.S. ground troops (by 1968 more than 500,000), a vicious chemical assault on the land and people (Agent Orange), a parade of political advsors and military geniuses picking bombing targets, a campaign of lies and phony statistics (body counts) masquerading as markers of eventual victory. Back home, the response —the war on the streets —focused on the draft that eventually sent 2.7 million Americans to Vietnam, 58,000 never came home, 304,000 were wounded, 75,000 of them permanently disabled.

One incident in 1968 captures the U.S. military’s warped thinking: on February 9, 1968, after a battle for the village of Ben Tre, an American officer told a reporter: “It became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it.” Lessons unlearned. In 2011, forty-three years later the U.S. toppled a sovereign head of state and destroyed, not a village, but a whole country in order to “save” it. That country —Libya.

War protests, bringing thousands of students and other disaffected young people onto the streets of college towns and cities, picked up steam after the Tet offensive of January 31st — an attack by Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops on key cities in South Vietnam, including the American embassy in Saigon. Although American forces eventually turned back the attack, the cat was out of the bag. The majority of Americans who up to this point had believed the official lies about approaching victory were shocked and disillusioned. In a poll conducted in February, a plurality of Americans thought the war was a big, fat mistake. By August, 53% agreed.

After the American public gave thumbs down to the war, events moved quickly and violently. February 8 —police in Orangeburg South Carolina opened fire on a peaceful student march at South Carolina State University (an historically black university) protesting segregation at Orangeburg’s only bowling alley. Three students died. The nine white officers who opened fire acquitted by a white jury. The protest coordinator convicted of inciting a riot. February 29 —the Kerner Commission, assembled to diagnose the ills of American society,  concluded: the U.S.] is moving towards two societies, one black, one white —separate and unequal.” March 12 —Senator Eugene McCarthy,the peace candidate, captured over 40% of the vote in the New Hampshire democratic primary. March 16 — Robert Kennedy entered the presidential race “[It] is now unmistakably clear that we can change these disastrous divisive policies only by changing the men who make them.” March 31— President Johnson dropped out of the presidential race declaring in a televised address to the county “I shall not seek and will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your president” (his approval rating in March, 36%, similar to Trump’s in 2018)

concluded: the U.S.] is moving towards two societies, one black, one white —separate and unequal.” March 12 —Senator Eugene McCarthy,the peace candidate, captured over 40% of the vote in the New Hampshire democratic primary. March 16 — Robert Kennedy entered the presidential race “[It] is now unmistakably clear that we can change these disastrous divisive policies only by changing the men who make them.” March 31— President Johnson dropped out of the presidential race declaring in a televised address to the county “I shall not seek and will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your president” (his approval rating in March, 36%, similar to Trump’s in 2018)

Five days after Johnson’s announcement, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. A shattered President Johnson mourned “Everything we’ve gained in the last few days, we’re going to lose tonight.” He was right. Over the next week riots broke out in 100 cities. The toll —39 dead, 2,600 wounded, 21,000 arrested.

Two months later, on June 5, 1968, Robert Kennedy became another high-profile victim of an assassin’s bullet, minutes after winning the California democratic primary. Two assassinations within two months exposed yawning fissures in American society along racial and ideological lines. Betrayed by the broken promises of the Great Society war on poverty an embittered and angry public, people of color, anti-war activists, draft resisters, vented their rage on the streets to be met with violent and deadly police force.

Meanwhile the U.S. military continued to spin its tales of lights at the end of tunnels and corners turned. Virtually every American but the president had concluded that reports of victory were a tissue of lies. What hope might have remained in the hearts of the tenacious few was erased when the “most trusted man in America,” reporter and journalist Walter Cronkite, originally an ardent supporter of the war, visited Vietnam to see for himself. On February 27, in his daily news broadcast to 28 million Americans he delivered his verdict.

“It seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate. To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past…the only rational way out… will be to negotiate not as victors but as honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy and did the best they could.”

America soon had its own domestic war—anti-war protestors faced off against the few remaining staunch supporters of the war, racial justice advocates traded barbs with white supremacists and student demonstrators held strikes and sit-ins protesting the war, the draft and racial inequality. The protest at Columbia University in New York City in the spring and the violent police response was breaking news all over the country. Meanwhile as the country came apart, LBJ was holed up in the White House on the orders of the Secret Service.

In the last week of August, at the Democratic National Convention, thousands of young protestors poured into Chicago determined to make their voices heard. To that end, they planned a series of non-violent demonstrations. The Chicago police, in those days a bunch of thugs in uniforms with weapons, had other ideas. Along with the Illinois National Guard, they clubbed, tear gassed and arrested hundreds of anti-war protestors, reporters and bystanders as the people cried “The Whole World Is Watching.” Indeed, “the revolution was televised,” as millions of Americans got an up close and sickening look at the carnage as they sat in front of their televisions.

Hubert Humphrey, Johnson’s vice-president emerged from the rubble as the democratic standard bearer. His loyal support of Johnson’s war policies and the third-party campaign of segregationist George Wallace who eventually carried five southern states, catapulted Nixon into the White House.

U.S. participation in the Vietnam War continued until 1973 when the U.S. finally declared victory (on specious grounds) and came home. In 1975, North Vietnamese troops captured Saigon and forced the South Vietnamese to surrender.

The Vietnam war ended but the polarization of American society and culture endures. Questions of right and wrong, good and evil, justice and injustice never left the stage. The fault lines of the sixties, war, including the Cold War, race, gender equality and human rights are as contentious today as they were a half century ago. The country once more appears to be coming apart at the seams. With no leadership in the executive branch, a Congress more intent on personal bottom lines than the public good, the steady erosion of democratic values, the strident militarism that infects domestic policing and the invasion of our personal space on the grounds of national security —troubling signs of a government that has lost the respect of a fair share of its people and resorts to “legal” repression of dissent to preserve its authority.

When the peoples’ voice goes silent, the authoritarian voice is the only sound left.

“What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.”

—Robert Kennedy hours after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

755 total views, 1 views today